Space is a loaded term, a notion simultaneously taken for granted and fixated upon. My space, your space, more space, forgotten space, lost space, threatened space, invaded space, outer space, unknown space. It’s the catalyst of mysteries, wars and futures. Space Wars, the aptly named Kuwaiti National Pavilion at the 14th Venice Architecture Biennale, pursues the complex notion of space in relation to its hinterland—non-city spaces—and its 4.67 million population within its 17,818-square-kilometres.

With an evolving territory and identity since the first traces of habitation in 8000BC, Katrina Kufer explores how the exhibition, despite enduring COVID-induced delays, powerfully but unsettlingly responds to the Biennale’s theme, How Will We Live Together? through the lens of Kuwait’s modernization and what it means for its (urban) future.

Curated by Aseel Al Yaqoub, Yousef Awaad Hussein, Saphiya Abu Al-Maati and Asaiel Al-Saeed, Kuwait’s second participation in a biennale focused this year on coexistence, and it brings a loaded history to the table. A crossroads of civilizations and trades from antiquity, the coastal nation’s geopolitical past saw Portugal and Britain’s extended presence, border conflict with Saudi Arabia, and a long, complicated, often antagonistic relationship to Iraq. It is a nation that has extensively deployed resources protecting and defining its space. But how does this relate to what it does with its space in formal terms? Kuwait, like many of the Gulf countries, emphasizes urbanization, rapidly developing its urban sprawl with its 2035 Kuwait Vision aiming to “Transform the country into a financial and commercial hub with a competitive private sector and a supportive State, maintaining social identity and balanced development.”

With entrepreneurship and innovation being pillars in Kuwait’s developmental goals, its architectural development is also an active player in the culture, architecture and design spheres within the wider MENA region, with what the curators describe as a number of “capital A” architecture projects, research and culture-based projects. Its topographical contributions self-reflexively challenge notions of space and architecture—along with those of many other Gulf nations, the curators note—that focus on the familiar metropolitan area rather than the remaining national landscape.

Urban growth has been a radical and exponential evolution since the 1970s in the Gulf, where the hinterland—zones typically dedicated to agriculture, military, resource extraction or heritage—incites mixed opinions, viewed as a space of untapped potential to a territory of cultural preservation. It is a polarizing space with varying degrees of—at times, unregulated—legislation and seemingly at-odds motivations of economy and heritage. “In Kuwait specifically, this relationship to the land varies throughout time,” explain the curators. “During the early 1900s, pre-1950s and pre the urban transformation of Kuwait’s metropolitan area, the relationship to the hinterland was a natural part of everyday life. It was not a space that was completely separate to the town, even if it was not utilized by all, it was recognized as an important facet of territory, protection, and heritage.” As new urban transformation saw it become a beacon for modernity, the curators continued, the hinterland became its opposite; a site representing the past and traditions that were then outgrown. This is the foundation upon which the pavilion’s exhibition poses its first questions and begins to attempt analysis of the hinter-urban status.

With the expansion and densification of the metropolitan area, the curators point out that people have become nostalgic for a time and space in which they could experience Kuwait in its expansive and natural beauty, citing camping as an extremely popular activity. Camping, however, resulted in the landscape enduring “more and more trauma from individuals driving over delicate ecosystems, leaving behind enormous amounts of trash, and treating the land very poorly,” lament the curators. “Thus, attitudes towards the hinterland shifted yet again from seeing it as a beautiful space of nature to thinking of it a personal wasteland in which one held no direct responsibility for what happened there.”

The oscillation of the hinter-urban dynamic makes it difficult to ascertain the Kuwaiti public’s current attitude towards and sense of connection with—or possibly lack thereof—the hinterland. It is also a space rarely discussed in architectural discourse. “These were spaces not well known to us at the beginning, and we were quite surprised to see the ways in which planning, development, and conservation have been approached across the hinterland,” the curators say. Given the neutrality with which they approached the Biennale’s theme, they were surprised by their discoveries.

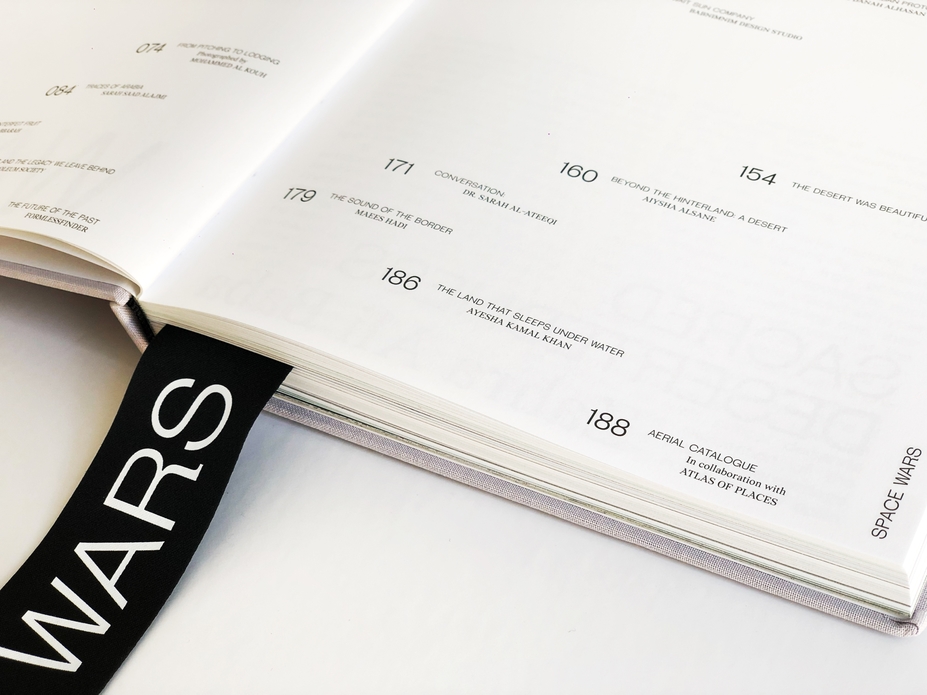

The findings, along with those from 23 local and international contributors, formed the pavilion’s three main physical elements and an accompanying publication that tackle the pavilion’s curatorial remit of spatial defences, offences or alliances that define the future of the landscapes under threat from extinction, overuse, domination or being forgotten.

Within the space is a 7.2×3.6-meter carpet that depicts the adjacencies spoken about throughout the work, a series of three film projections, and two tables that houses various research products compiled during the project.

The large carpet consists of three individual carpets woven together, each one filled with hand drawn elements that depict discovery, interpretation, and projection relative to reality on the ground. As the elements change over time across the carpet, their location directly ties to the geography of Kuwait as it currently exists.

Directly across from this are three film projections that also showcase discovery, interpretation, and projection, however, through archival footage, satellite imagery, and projections from our contributors. The tables, one large aluminum table in the middle and a smaller podium table adjacent to it, showcase research products such as desert truffles, historical maps, interview transcripts, and more that were vital to the process of Space Wars.

The network of intersections formed by interpretations from disciplines including art, architecture, military, history and ecology, among others, illuminated further points of inquiry. “It was very interesting to see the types of programmatic adjacencies that we began to explore, such as moments where houses were sharing a fence with an active oil refinery or when a mega highway project came to an abrupt end because it was slated to have gone directly through a valuable archaeological site,” they note. “While these moments certainly highlighted a lack of communication or coordination across various parties involved, other beautiful moments emerged as well. Many people who were lucky enough to have experienced Kuwait’s hinterland before continued development speak of its lush green landscape, filled with flowers and wildlife. While it’s nearly impossible to find this today in publicly accessible areas, it continues to exist in those spaces which have been cordoned off from public use. It highlights that this can still exist, it just takes effort on everyone’s part.”

Space Wars pinpoints pockets of discovery, memory and hope as much as subtly implied bleakness in what an urban future holds. It opens deeper, perhaps more unsettling questions on to what extent it affects the broader public, and what effect they in turn will have on the hinterland. It is an oscillating reality over a geography that inevitably forms national identity and sets the tone for forthcoming economic prosperity. For all that the hinterland means—or could mean, as a symbolic, physical, social, political and economic space—to Kuwait, the underlying question seems to be at what moment will coexistence between these competing motivations no longer be an option, and in the space wars between the hinterland and the urban, which side will have to give way?

The Kuwait National Pavilion, commissioned by Zahra Ali Baba from Kuwait National Council for Culture Arts and Letters, is open until 21 November 2021 at the Venice Architecture Biennale.

...the curators point out that people have become nostalgic for a time and space in which they could experience Kuwait in its expansive and natural beauty.

About The Editor

Katrina – arts, culture and lifestyle writer and editor (BFA Fine Arts, Parsons the New School for Design; MA Contemporary Art, Sotheby’s Institute of Art) – has lived in 16 countries and written for a multitude of prestigious publications in the MENA region. Based in Dubai, Kufer is interested in observing new environments and exploring cross and inter-cultural connections.